We might consider academic freedom as secured after the 1938 resolution. However, the real situation is far more complicated than our imagination. This part of the story is about the release of two key documents and their impact on academic freedom. They are both relevant to oaths.

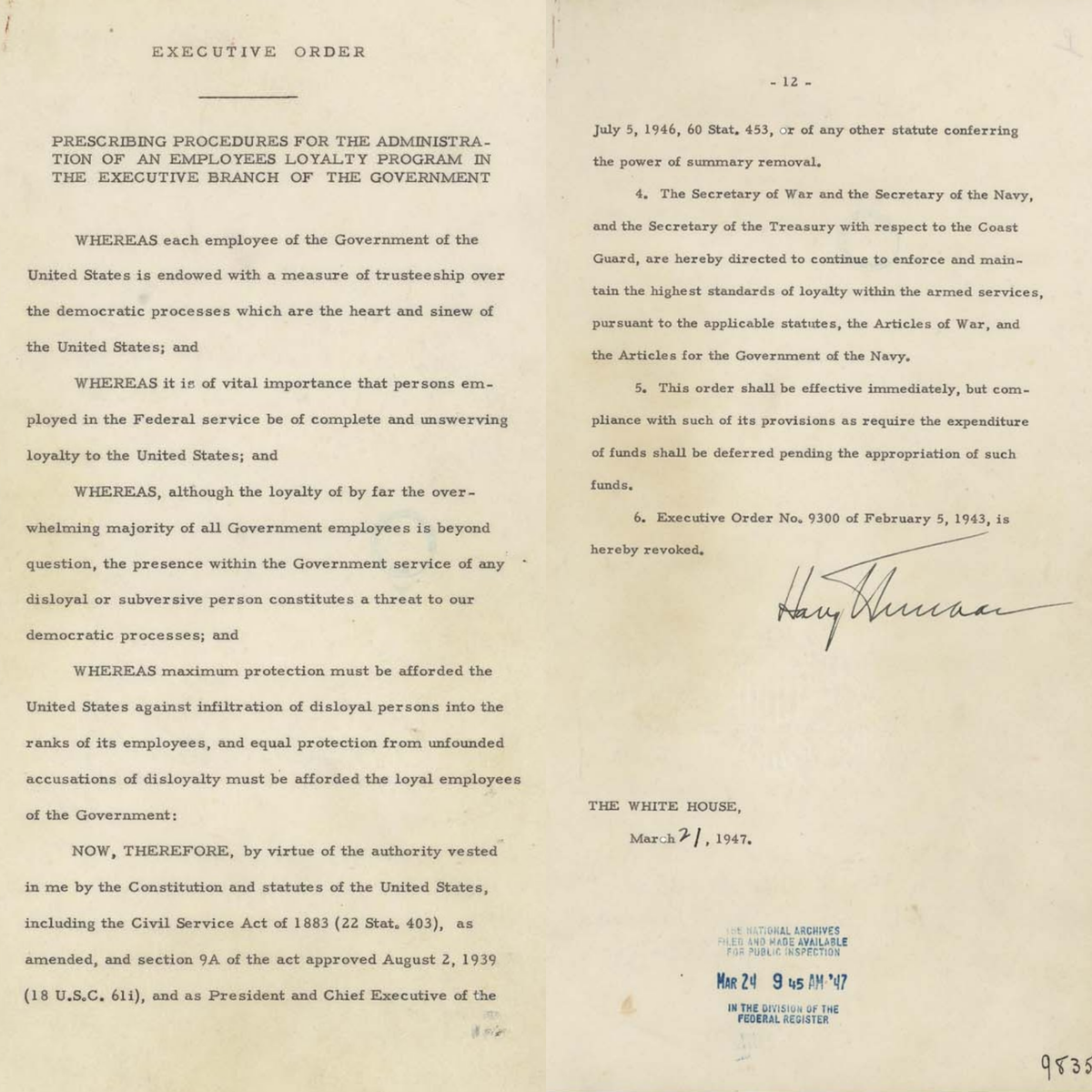

Executive Order 9835

Executive Order 9835 was issued on March 21, 19471.

According to an article in 1949, it dealt with “ the way employees supposedly think instead of the way they act3. Also mentioned was that a federal employee may be fired due to a “ sympathetic association”, which is impossible to define accurately.

A 1949 article quoted the words of Dr. Beck, one of the speakers at a Minneapolis Town Meeting2, which went as “The Communist threat to free discussions at the universities of this country is greatly exaggerated”. The nation’s commitment to individual liberty was severely questioned.

Loyalty Oaths and the University

On July 11, 1949, president J. L. Morrill talked about “communism and the colleges” at the American Alumni Council meeting4. He emphasized the importance of academic freedom and claimed a proved patriotism in universities. This should be considered representative of the faculty’s thoughts.

And Morrill wasn’t alone. Several student-faculty organizations, including YMCA, YWCA, the Young Democratic-Farmer-Labor club and the University branch of AAUP, organized a committee on academic freedom to “sell the idea of academic freedom to the legislature”5.

In 1953, the Association of American Universities published The Rights and Responsibilities of Universities and Their Faculties6. Part IV, The Present Danger, stated that “academic freedom is not a shield for those who break the law”. The document also condemned Russian Communism intensely as if to emphasize the loyalty that universities hold.

These words deemed it necessary to evict criminals if academic freedom was to be protected. The U of M followed soon with another document which was totally a copy of the AAU document7.

As it turned out, the All-University Congress adopted a resolution in 1954, claiming that most educators are innocent. The Congress “recognize the right of the United States to conduct investigations” but “condemn the methods”. The document stated that investigations shall only be made by “a tribunal of one’s faculty colleagues”, much similar to what was stated in the 1938 U of M resolution8.

Good things happened with regents of the U, too. They reaffirmed academic freedom in 19589. They endorsed Morrill’s statements and defined faculty’s opinions as “not censorable”. Their determination to defend free speech was clearly seen.

National Defense Education Act (NDEA)

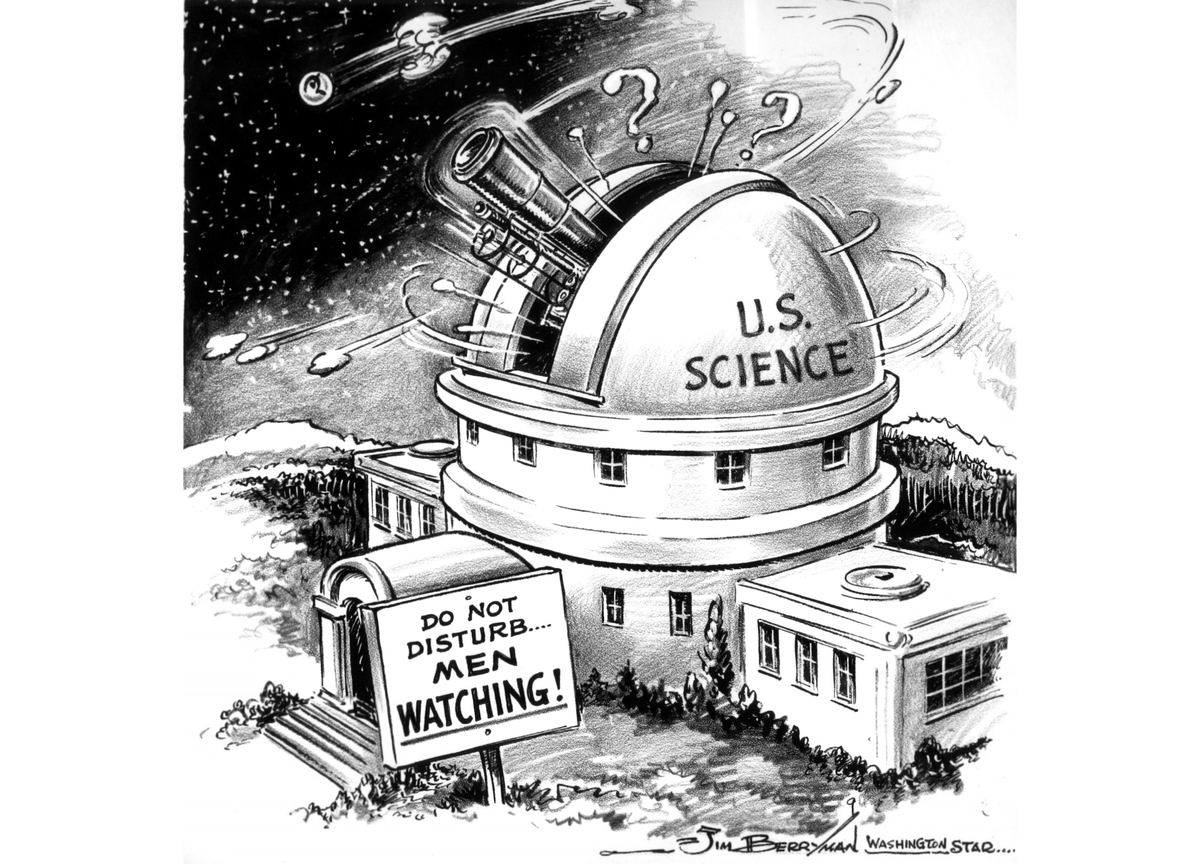

The Soviet Union’s successful 1957 launch of Sputnik, the first artificial satellite, spurred Congress to pass the National Defense Education Act (NDEA) of 1958 perceiving an urgent need to train Americans in skills for Cold War defense10. The act linked availability of loans to an oath that swore allegiance to the country11. This was completely incoherent with public opinion. National officers of the A.A.U.P. opposed it in a letter and publicized it.

Nevertheless, some people at the U might adopt different perspectives. Minnesota Daily stated that three out of five members of the Committee on Academic Freedom and Tenure argued for the oath since withdrawing from the program would “foreclose the student’s freedom of choice"12. This added on to the governmental pressure that the University was suffering from.

Nevertheless, the U of M stood against these oaths as a whole. Oaths turned out to be a great threat to academic freedom during the Cold War. Though the social situation changed afterward, it did not mean that people had won the fight.

Acadamic Freedom at the University of Minnesota

1870-1914 | 1918-1940 | 1945-1975 | 1975-present | Citation